Trademark Dilution: “Famous” Trademarks Get Enhanced Legal Protection

© 2006, Gallagher & Dawsey Co., LPA

November 2006

A case with Sixth Circuit roots has led to the unusual step of a Congressional overturning of the Supreme Court on a trademark matter, with implications for large and small trademark holders alike.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Moseley v. V Secret Catalogue, Inc. (537 U.S. 418 (2003)) involved a small store owner’s attempt to use the name “Victor’s Little Secret” against the protests of the giant Victoria’s Secret company. The district court in Kentucky, finding that the record contained no evidence of actual confusion between the parties’ marks, concluded that “no likelihood of confusion exists as a matter of law.” It entered summary judgment for petitioners, Victor and Cathy Moseley, on trademark infringement and unfair competition claims. However, as to a claim brought under the 1995 revision of the Trademark Dilution Act of 1946, the court first found the two marks sufficiently similar to cause dilution, and then found “that Defendants’ mark dilutes Plaintiffs’ mark because of its tarnishing effect upon the Victoria’s Secret mark.”

The Sixth Circuit affirmed, and the Supreme Court was confronted with a growing Circuit split on the issue as to whether trademark dilution required an actual lessening of the ability of a mark to distinguish goods, or whether more diffuse “tarnishment” of a famous mark might suffice. The evidence showed that while those who saw “Victor’s Little Secret” thought of an association to Victoria’s Secret, there was no evidence that they had formed a lesser opinion of the Columbus retailer as a result. With no lessening of the capacity of the Victoria’s Secret mark to identify and distinguish goods or services sold in Victoria’s Secret stores or advertised in its catalogs, the Supreme Court held that the text of the Trademark Dilution Act “unambiguously” required a showing of actual dilution, rather than a likelihood of dilution, such as might be posed by trademark tarnishment.

While stating that it was not establishing a requirement for actual financial loss to bring a dilution action, the Court was unclear as to how the owner of a famous mark might prove dilution. If, as it has been written, dilution is a slow and gradual process like a cancer that destroys the value of a mark, significant real damage could be done before traditional proof of this damage might be available. Trademark owners, backed by the International Trademark Association (INTA) began lobbying for congressional enactment of a stronger anti-dilution statute. The resulting Trademark Dilution Revision Act (TDRA) of 2006 was recently passed and signed into law by President Bush.

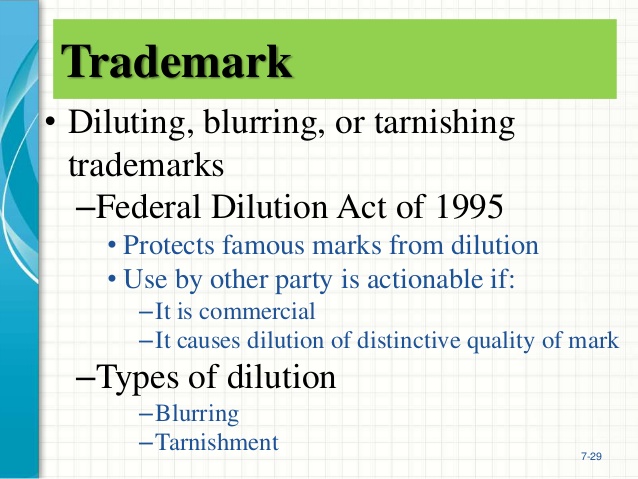

The law overturns the decision in Moseley, and establishes two kinds of dilution: dilution by blurring and dilution by tarnishment. “Blurring” is defined as an association arising from the similarity between a mark or a trade name and a famous mark that impairs the distinctiveness of the famous mark. “Tarnishment” is an association arising from similarity that harms the reputation of the famous mark. Therefore, the Moseley situation would fall within “tarnishment,” and the owners would have a cause of action for dilution without having to prove a loss of their mark’s ability to differentiate. Without an actual damage requirement, owners of famous marks should now have an easier time obtaining injunctions to protect their marks.

In response to First Amendment concerns regarding the possible breadth of interpretation of what might “harm the reputation” of a mark, exemptions were placed in the law for “fair use,” such as comparative advertising, parody, and criticism; and exemptions for all forms of news reporting and commentary, and any non-commercial use of a mark.

Reaching beyond the Moseley decision, the law makes other changes affecting trademark law. The law defining what makes a mark “famous” was never clear, and the TDRA, in addition to providing that courts may consider “all relevant factors,” now provides four suggested considerations in making a determination of “fame.” These are 1) the duration, extent, and reach of advertising and publicity of the mark; 2) the amount, volume, and geographic extent of sales under the mark; 3) the extent of actual recognition of the mark; and 4) whether the mark was federally registered.

The TDRA also stops what had been a growing trend to accept fame within niche markets as satisfying the requirements for a famous mark. A famous mark must now be “widely recognized by the general consuming public of the United States as a designation of source.” This may be a significant setback to owners of marks that are well-known in the specialty markets that they serve, but that are not well known to the public. If the value of a mark is its recognition within a specialty market, dilution could destroy a niche owner’s value in a mark without leaving any legal recourse.

The TDRA is not limited to trademark enforcement, but makes changes in the way trademarks are examined and registered. A likelihood of dilution, either by blurring or tarnishment, is now grounds for opposition to, or refusal of, a trademark application, as well as grounds for cancellation of a registered trademark. This will make it easier for owners of famous marks to block dilution at earlier stages. Overall, the law is certainly a win for owners of nationally known marks, but a possible loss for specialty brands, and a definite change and clarification in trademark law.